The following is an excerpt from Markku Kuukasjärvi's paper Dark Tourism-the Dark Side of Man. Part of the reason this research interests me has to do with its possible complication of the seeking out of experiences of hauntological psychogeography. Does thanatourism exist on the same continuum? Afterall, I myself list "bunker archaeology" as an interest on my profile, and those who I've shared travel/exploration experiences with know all about the sites we visited, the historical legacies of which were mapped out/researched carefully before we got there. But as I have future plans for a post on "bunker archaeology", I won't speculate too much about the possible connections here.

I do think though that the increasing Australian limit experience of walking the Kokoda Track may be of a slightly different order to much of what the following article characterises as "dark tourism", letalone the increasing attendance of the Gallipolli commemorations. Reflecting on one particular barrister I met, and then a revealing article passed onto me by my brother in The Financial Review, I was mortified by the existence of the pursuit of limit experience in all aspects of the lives of a substantial number of these people, which they had originally inherited from their jobs. Many of them were riding 100s of kms per week at odd hours, that is, when they weren't competing with each other to be the first in the office, and the last to leave. The article ruefully noted how many organisers of "fun" cycling charity events had become exasperated by these kinds of participants pestering them for details of their "times". Not coincidentally, many of them had taken on Kokoda as a kind of personal endurance test. One wonders if any connection to the original historical context is more to do with the kind of "battlefield nationalism" the odious Prime Minister John Howard has propagated: simply going to work requires similar endurance qualities to the ANZACS, a "band of brothers", as more expansive conceptions of social capital are abandoned in favour of amoral familialism in a neoliberal social Darwinian culture ("survival of the fittest").

Notwithstanding these qualifications in an Australian context, the following research is, in my view, promising in many respects, and no doubt widely applicable:

Death and the society

In eighteenth-century Europe and England, death was everyone's intimate acquaintance, constantly on view. Child mortality rates were extremely high. Crowded living in unsanitary conditions, malnutrition, famine, disease, and accidents ensured life's unpredictability from day to day. Executions were also public. Well into the nineteenth century, an execution day was a holiday, and schools were let out; it was commonly believed that the sight of punishment would deter future criminals. The bodies were often displayed for a long while, the flesh decaying before people's eyes.

Late in the eighteenth century, death actually began to recede in many Western countries, if imperceptibly at first, and attitudes to it changed. Over time, social, religious, and medical changes made dying and death gradually withdraw from view; by the mid-twentieth century they became virtually invisible in most large metropolitan centers, especially in America and England.

Once the cemeteries were shifted away from city centers, the rural cemetery was turned into a delightful garden and the old casual acquaintance with dead bodies was transformed into a spectacle or viewing opportunity. In Paris, people idly dropped in on the morgue, where the door was always open, if they were passing by, and the catacombs, where the bones that had welled up from earlier cemeteries were arranged in ranks and galleries, were popular sites for tourists. (Goldstein 1998: 27-28)

In historical terms, in the sense of visiting sites of death and disaster, dark tourism has long roots that date millennia backward in time. Public entertainment and presentation of death for retribution and public intimidation have long been practiced throughout contemporary societies. During the past three centuries, the withdrawal of death from the public scene has increased death-related mysticism and its deep-rooted fascination amongst the common people.

Now, what and when exactly is dark tourism? Some scholars limit the phenomenon only to the modern times, based on its relation to the post-modern society. What is the nature of dark tourism? These questions we try to answer through different definitions of the phenomenon.

Varying definitions

Being a relatively new theme in academic writing, there are few attempts to define dark tourism. They are not unified in scope and extent, so in order to get a complete picture of what dark tourism is all about, we will investigate the definitions one by one.

Definition by Lennon and Foley

The first researchers to bring dark tourism to the eyes of the academic society were John Lennon and Malcolm Foley with their book Dark Tourism: The Attraction of Death and Disaster. In only seven years, they had stimulated significant academic attention, and had even merited an encyclopedia entry for thanatourism / dark tourism (Singh 2005:63). The term dark tourism was coined, as a means of describing "…the phenomenon, which encompasses the presentation and consumption (by visitors) of real and commodified death and disaster sites" (Lennon & Foley 1996: 198).

According to Lennon & Foley, dark tourism is principally an intimidation of post-modernity. This means the events and places in history, that now have turned to dark tourism destinations, introduce doubt and anxiety about modernity in the viewer’s mind. How did the unsinkable Titanic, the technological pinnacle of the time, sink after all taking 1500 passengers down with her? Why was Martin Luther King Jr., defender of peace, equality and modern thinking itself, assassinated? Moreover, how could the civilized and cultured society of Germany systematically murder 1,6 million Jews in the Second World War?

A more recent similar example could be the massacre in Rwanda, where roughly a million ethnic group members were iniolated in just a hundred days in 1994. The most striking fact outside the massacre was the ineffectiveness of the United Nations and its Western members in particular. Countries like United States, Belgium and France all declined to intervene or speak out against the planned massacres prior to the event actually taking place.

In other words: things that shouldn’t happen in the modern world do happen. Sometimes it is possible to prevent them from happening, and yet it is not done. This introduces the apprehensive question: are we safe in this world after all, and moreover, can we feel safe in ourselves?

Each of the forementioned events and their numerous respective memorials, museums etc. receives significant tourist attention. Each of these are dark tourism destinations with apparently dark connotations.

Lennon & Foley set two more preconditions for dark tourism (in addition to the threat on post-modernity): firstly, that global communication technologies play a major part in creating the initial interest and secondly, that the educative elements of sites are accompanied by elements of commodification and a commercial ethic, which approves taking the opportunity to develop a tourism product. The first means instantaneous media coverage of events, local or global in scale, and hence introduces the collapse of time and space. The latter suggests that apart from being an arrant source of education, a dark tourism site carries the capacity of financial benefit that is being exploited. These conditions are sufficient to satisfy Lennon & Foley’s definition of dark tourism.

These limitations exclude, for example, roughly the sites of battle and other events prior to the start of the twentieth century due to the chronological distance, from being labeled ‘dark tourism’, the reason being that they do not induce anxiety about the present-day society and the direction it is heading. These events are just too far back in time for us to really grasp it.

Seaton’s definition

Tony Seaton coined a similar label in his definitive article, From Thanatopsis to Thanatourism: Guided by the Dark. In it, he describes thanatourism as being, "…travel to a location wholly, or partially, motivated by the desire for actual or symbolic encounters with death, particularly, but not exclusively, violent death, which may, to a varying degree be activated by the person-specific features of those whose deaths are its focal objects" (1996: 234-244).

The definition of thanatourism focuses on the travel motivation, which determines whether -and to what degree - the travel is thanatourism. The actual or symbolic encounters with death constitute the core of the thanatourism phenomenon. If there are special features to the death of a person or the person himself whose death site is visited, it may by its own right boost the desire to visit the site. For example Graceland, the home of Elvis Presley in Memphis, US, celebrates the memory of a superstar, whose loyal fans and other tourists still visit the rock and roll legend’s home decades after his death. Graceland mansion now harnessed for another purpose; it has been turned to a museum and a centre for commemoration. For many, the reason to ‘meet death’ is not the main purpose of travel to this destination.

Seaton furthers his definition by adding two factors. First, thanatourism is behavioral; the concept is defined by the traveler’s motives rather than attempting to specify the features of the destination. Unlike Lennon and Foley’s concept, Seaton recognizes that individual motivations do play a role in death and disaster tourism. Secondly, thanatourism is not an absolute; rather it works on a continuum of intensity based on two elements. First, whether it is the single motivation or one of many and secondly, the extent to which the interest in death is person–centered or scale–of–death centered. Figure 6 illustrates Seaton’s thanatourism continuum.

Figure 6. Seaton’s Thanatourism Continuum. Seaton (1996)

Seaton suggests, as presented in Fig. 6 on the left, that dark tourists whose travel motivation has a weak thanatourism element, have a very person-centered interest in death. The main motives for such travelers are commemoration and respect for the dead. Dark tourists with a strong thanatourism element (on the right in Fig. 6) are defined as having a generalized interest in death and that for them, meeting death is the sole purpose of travel. Scenes of disaster would be a favored destination for such travelers.

Rojek and Black Spots

Chris Rojek coined the third term affiliated with the concept of dark tourism. His expression, black spots, refers to the "…commercial developments of grave sites and sites in which celebrities or large numbers of people have met with sudden and violent deaths" (1993:136). Rojek’s approach to black spots comes nearer to Foley’s & Lennon’s definition of dark tourism with commercialized utilization of the site. It seems that commercialization is indeed regarded as an important component of a dark tourism destination.

Dark Tourism by Philip Stone

Philip Stone, the editor of the Dark Tourism Forum, wrote a definition of dark tourism, which is probably the simplest of the ones presented. He states: 'Dark tourism is the act of travel and visitation to sites, attractions and exhibitions which has real or recreated death, suffering or the seemingly macabre as a main theme.' (www.dark-tourism.org.uk) This definition, as well as Lennon & Foley’s and Rojek’s definitions, focuses equally on the dark characteristics of the destination itself, not the travel motivation of the tourists visiting the site. Apparently, we have several terms to describe the same phenomenon, but there are also two clearly distinct approaches.

This leads us to a question: is dark tourism demand-driven (by the taste of dark tourists) or supply-driven (the allure of the destinations), or is it possibly a combination of the two? In addition, we must ask if it is the tourist’s purpose of travel that creates a makes the travel dark tourism or is the destination itself the determining factor to define the phenomenon.

Commercialization and different shades of the dark

It is the mystery of death that may come to mind when thinking of what attracts tourists to visit a dark tourism destination. But also marketing schemes are being implemented, the sites being partially commercial of nature, which also reinforces the pull factor.

"If you’re looking for fun things to do in Memphis and enjoy visiting celebrity homes, don't miss touring Elvis's 14-acre estate in Memphis, Tennessee" (www.elvis.com). At Graceland, several Elvis-related packages are being offered from the regular visit to the mansion up to weddings. There are Elvis gift shops to buy souvenirs, the Elvis Christmas Celebration is a package for the whole family and Elvis Wedding Events make it possible for couples to get married in a chappel very close to the King’s mansion.

Clearly the multitude of supply and marketing efforts has an effect on the tourist’s travel decision, especially in highly commercialized dark tourism attractions, like that of Elvis. In contrast, at the museum and concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau, where the most important thing is realistic interpretation of the history, the commercial character is not so apparent. For legislative reasons amongst others, admission to the estate is free of charge. Naturally some profit-producing services are included, such as guide-service and selling of books and articles related to the Holocaust, but, due to the historical significance of the site, it would be out of context and beyond good practise to commercialize it further.

It appears that the ‘darkest’ of dark tourism destinations are relatively little commercialized, whereas such death sites of popular culture icons like Elvis with less ‘dark’ associations have a broad range of support services and products. Of course, not all celebrity death sites or sites of ‘lighter’ nature are heavily commercialized, however, an apparent link can be found between the historical and political sensitivity of the site and the level of commercialization.

It has been argued that several stages of darkness exist within the field of dark tourism supply (Miles 2002: 1175-1178). Miles proposes there is a crucial difference between sites associated with death and suffering, and sites that are of death and suffering. Thus, according to Miles, the product (and experience) at the death camp site at Auschwitz-Birkenau is conceivably darker than the one at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC. (Stone 2006:151)

Figure 7. A dark tourism spectrum: Perceived product features of dark tourism within a ‘darkest-lighest’ framework of supply. Stone 2006.

The part above the scale-line in Fig. 7 shows the ‘nature’ of the dark tourism destination, that is it measures its sensitivity or the political and historical influence, and the descriptions under the continuum describe different characteristics of the site. With one additional measure, the level of commercialization (placed at the bottom in Italics), we can more accurately decide to which end of the continuum an individual dark tourism destination should be placed.

Looking at the scale, the link to the travel motivation becomes more evident: the more sensitive the site, the more motivation veers toward education and commemoration and the more authentic is the encounter with death. The dark effect is at its strongest at the left end of the continuum and respectively weakest at the right.

Dark sun resorts

There is a kind of dark tourism destination that has all the characteristics of a holiday destination and also features of a dark tourism destination. Outstanding examples are the holiday paradises wiped out by the tsunami in 2004. Before the destructive waves struck the shores of Thailand, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and many other countries, the Christmas season was at its peak.

Then, in one short instant, these glamorous oriental tourist attractions turned to vast cemeteries. Nearly 300 000 people lost their lives, amongst them thousands of tourists. Much of the tourism infrastructure was destroyed at the same time.

The holiday resorts were quickly rebuilt, however. In Phuket of Thailand, for about eight months after the tsunami, most hotels had less than 10 % occupancy. One year after the tsunami, most of the island’s hotels were back to business, though many were not doing very well. But then there are places like Phi Phi Don island, a 90-minute ferry ride from Phuket, where the waves' full fury was felt. Rebuilding on Phi Phi Don had barely begun in January 2006; the tragedy's legacy was all too apparent. Official records show 721 died in Krabi province and many of them are still missing. Tourists are gradually returning, but some are still hesitant; they wonder if dead corpses can still be found floating in the sea. (Beyette 2006 in Los Angeles Times)

Tourism is coming back to the rebuilt resorts in Thailand. Sun is still shining, people sunbathe and swim in the sea. Children build castles of sand. The ‘Tsunami escape route’ –signs are the only visible remnant of the total destruction. Everything seems to be back to normal, but something has changed. Most tourists still come for the sun, but there is also curiosity amongst them to see the site of destruction for themselves. Many have seen the shocking videos and pictures of the destruction and at least heard of the rottening corpses floating in the sea.

These beautifully restored beach resorts are actually places where hundreds, or even thousands of people died very recently. Amongst the sun-seekers there are their friends and relatives, coming to pay respect to the victims of the tsunami. The places themselves have not changed, but for some visitors, they have changed forever.

Can we categorize these destinations as dark tourism destinations? Obviously they are very much commercialized, but the commercialization has nothing to do with the tsunami. Reflecting against Lennon & Foley’s criteria for dark tourism destinations, they neither raise questions about the modern society, the cause being a natural phenomenon. It did bring about tremendous suffering and it required enormous casualties, but even so, it does not shake the image we hold about the man-made world (societies, cultures, et cetera). But these destinations do match the general description: "visiting sites of death and disaster".

These destinations have sun seeking and relaxation as the main theme, not death and suffering, so they can neither measure up to Stone’s definition. It appears that – in the scientific reign at least – tourist destinations that have been destroyed by a natural disaster do not qualify as dark tourism destinations. In tourism research, for example, it would be difficult to measure the amounts of leisure tourists visiting these sites, when the number is obscured by estimations about dark tourists at the same site. However defined, one thing is for certain: there is a dark element to each of these sites. Though these destinations cannot be called dark tourism attractions, with some degree of certainty we can assume that there are dark tourists who visit these sites inspired by just this element.

Dark tourism could be summed up as: "The act of visiting places with death, suffering and disaster as the main theme, driven by both the supply of the destination and the visitor’s interest in its extraordinary features". Furthermore, it is important to emphasize the multitude and diversity of dark tourism attractions, all of which by no means serve similar functions and share the same characteristics. As proved by our last example, the tourist may indeed be a dark tourist (visiting a place that, to him, is of death and dying), even though the destination does not qualify as a dark tourism destination.

Either one of the definitions described in this chapter can neither be called wrong nor the absolute truth; they are simply slightly different ways to look at the same phenomenon.

Types of Dark Tourism

There are many forms of dark tourism supply. Some are physical destinations where atrocities and dying have actually taken place; some are purposefully built in another location to commemorate such events. There are dark tourism products where the tragic event is being re-enacted with the tourist participating in the process. Some destinations offer more educative value, some exist mainly for entertainment. In this chapter we focus on the types of tourism on the supply side of dark tourism. In effect, we focus on plain distinguishable characteristics shared by a number of dark tourism destinations. As shown before, destinations can be divided into different ‘shades’ of darkness for example, depending on many factors that affect the dark tourist’s experience. In this chapter only the surface of the dark tourism destination is being evaluated, the different effects that the dark tourist may experience there are left to be introduced in the chapters to come.

Destination categories

The following categorization was developed by the author based on dark tourism literature and few already established dark tourism categorizations (Dann 2001; Stone 2006).

A rough cut of the main different types of dark tourism could be as follows:

Seeing places of mass murder and genocide

Going to museums related to death

Visiting graveyards and cemeteries

Going to dungeons

Battlefield tourism

Slavery tourism

Taking part in re-enactments of tragic events.

The first category of dark tourism, the sites of mass murder and genocide includes sites such as Auschwitz and the Killing Fields of Cambodia and other places where a large number of people have died. The place of the twin towers struck down by terrorist attacks in September 11 2001 that is now known as Ground Zero, also falls into this category of dark tourism. These places also belong to the darkest shade of the dark tourism continuum with closest contact to dying.

The second category, museums and exhibitions, includes any genocide museums, and museums associated with wars. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington and the Yad Washem Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem are probably the most renowned examples of this kind of museums. Also the Imperial War Museum in London, dedicated to viewing the war history of the United Kingdom from the First World War till present, belongs to this category.

The third category is visiting graveyards and cemeteries exclusively or as a part of the travel itinerary. It is claimed that the presence of death and the abundance of related symbols like gravestones and other elements give the dark tourist pleasure that is rooted in Gothic or Romantic art and literature. Père-Lachaise is the most famous of the 20 cemeteries in Paris. Beyond its primary function, this famous Romantic-inspired necropolis has become an open-air museum and pantheon garden.

The dark tourism sites in the fourth category, Dungeons, are usually rich in visual display and are built much for entertainment purposes. The London Dungeon simulates horror from history, recalling events of atrocities from the past. You can journey back to the darker side of European history. The Dungeons often include portrayals of how the punishments for crimes from executions to beheadings and torture were practised in the past. Celebrity death sites can be mentioned as a sub-category of its own. This means the death sites of famous individuals that are still objects of frequent tourism visitation. Dead celebrities like Elvis Presley, John Lennon, James ‘Jimmy’ Dean and Marilyn Monroe still live in the memories of the many thousands of visitors that visit their death sites each year.

The fifth category of dark tourism, battlefields tourism, means visiting locations where battles, both great and small, have been fought. Tour operators arrange trips specifically for this purpose or as a part to a more extensive travel plan. The experience of standing on the ground where soldiers fell and blood was shed can bring the reality of war close to the dark tourist. Many tourists who visit battlefields are war veterans coming to pay respect to their comrades and maybe to bring a tragic period in his life to an end. Some tour operators even arrange trips to active battlefields, like those in Israel or Afghanistan. (www.dark-tourism.org.uk)

Slavery tourism, also known as ‘roots tourism’, involves visitation of sites that were formerly used in the trans-Atlantic slave trade or that can bring up strong memories about slavery. This is the sixth category of dark tourism. In Africa, guided tours typically focus on the perspective of slaves and the tragedies they were made to endure. Some of the most famous of these destinations are Cape Coast Castle and Elmina Castle in Ghana, and Gorée Island in Senegal. (Ann Reed: www.dark-tourism.org.uk)

Re-enactments are a specific kind of dark tourism, and the seventh category in the listing. Here the tourist is a part of the dark tourism product itself. For example the re-enactment of the Battle of Hastings is a yearly event at Battle Abbey in Battle, East Sussex, UK, recreating the Battle of Hastings. It takes place every year on the weekend nearest the 14th October on the site of the historical battle. Another example of a dark tourism re-enactment is the replay of the death of President John F Kennedy in Dallas, Texas. There is a tourism product built around the assassination in which a presidential limousine will take you through the same route as it did on November 22 in 1963. The sounds, the crowd’s cheers and the gunshot are all played in ‘real time’ just as it happened. Even the speeding to the hospital is included in the experience. (Foley & Lennon 2000: 98) The motivation of a tourist taking this kind of trip can just be guessed, but it is as close as it gets to reliving the event.

Dark Tourism in numbers

Even though dark tourism is a growing phenomenon, it is only a small fraction of the worldwide tourism sphere. For example, compared to the most popular tourist attraction in Paris (being the most visited city in the world), Disneyland Paris, even the most visited dark tourism destinations fall far behind. About 12 million people visit Disneyland Paris each year. (www.unwto.org) However, if we view the phenomenon from the supply-perspective, the situation looks quite different. Smith stated in her research about war and tourism: "…despite the horrors of death and destruction, the memorabilia of warfare and allied products…probably constitutes the largest single category of tourist attractions in the world" (1996:247-264). In the following, we shortly glance at some of the most popular dark tourism destinations today.

The US Holocaust Memorial Museum has received 24.1 million visitors as of April 1993 till September 2006. This amounts on average to 1,7 million visitors per annum. The visitors have amongst them 34 % school-aged children, 12 % are international visitors, and non-Jewish visitation to the museum is as high as 90 %. Also over many heads of state and over 2,700 foreign officials from 131 countries have visited the museum. (www.ushmm.org)

In 2004, nearly a million people visited the Anne Frank memorial museum in Amsterdam, Holland. The same year, Auschwitz-Birkenau received over half a million registered visitors, of which roughly one third were Polish citizens. The share of international arrivals at Auschwitz has increased steadily from 47 per cent in 1997 to 66 percent in 2004. The statistics for Auschwitz are gathered at the gate of Auschwitz-Birkenau, and it is optional for individual visitors to register. Hence the actual figure is thought to rise up to a million visitors per annum. All groups are required to register before entering the museum / camp. (www.annefrank.org; www.auschwitz.org.pl)

Graceland welcomes over 600 000 visitors each year, with an economic impact of 150 million dollars on Memphis per year (The Guardian, July 26, 2002). The London Dungeon, also belonging to the more easy-going end of the destinations, welcomes yearly over 750 000 visitors. Other dungeons affiliated to the London Dungeon have been built elsewhere in Europe too, like in Hamburg and most recently in Amsterdam in 2005.

For some destinations, dark tourism can be financially very beneficial. All dark tourism destinations can be said benefit financially from tourism to some degree; some benefit more, some less, depending on the commercial nature of the destination. But the very significant aspect of dark tourism is the education it delivers to the millions of visitors going to a number of destinations across the world. The educational aspect is often central for dark tourism attractions.

Until now, we have become familiar with definitions of dark tourism, its history and its different types, and introduced death’s place in society. Death is one of the keywords in this paper. Along with the next chapter we move to the focal point of this work, the dark tourist’s travel motivation, which has much to do with concepts like curiosity and fascination of death.

Motivation to Dark Tourism – The Intrigue of the Dark Side

It could be argued that we have always held a fascination with death, whether our own or others, through a combination of respect and reverence or morbid curiosity and superstition. However, it is (western) society’s apparent contemporary fascination with death, real or fictional, media inspired or otherwise, that is seemingly driving the dark tourism phenomenon. (Stone 2006: 147)

A number of theories probing into the tourist’s mind have been developed and we hereby investigate those that are most relevant in their ability to explain the appeal of death and dying in the consumer. First, let’s have a look at the effect media has in creating the interest.

The contribution of media

As already mentioned in chapter 3.2, death had started to recede from public view in the late 18th century. The trend continued increasingly so that by the mid-twentieth century death had become virtually invisible, particularly in the Western metropolises.

The written media responded in the nineteenth century by bringing to the fore not only more depictions of death but depictions of more secular, violent, and essentially uninstructive death. This meant that the entertainment value of death had surpassed the value of its educative / informative counterpart.

What's more, the illustrated newspaper exponentially increased the number and proportion of depictions of accidents and natural disasters: railroad crashes, shipwrecks, explosions and floods. These had neither religious significance nor redemptive force, but since they might happen to anyone, they may well have contributed to general and unspecific increases in anxiety. Disasters are undeniably news, but in other respects the papers were only responding to a fascination with accounts of violent death that ran alongside the movement, which attempted - if not to entirely wipe out - at least to beautify the end of life.

The news, which was heavily invested in descriptions and images of violent death from the beginning, has never ceased to be so; the general opinion today is that it has gone ever farther in the same direction. (Goldstein 1998: 39-40)

Media feeds the hunger for death, and the hunger grows the more it is fed. Viewers get used to seeing death, imagery becomes increasingly violent when closer and more powerful encounters with death are sought after. We are in a treadmill with no signs for exit. Now let’s get back to the core of the situation: what is it that makes death and violence so appealing in the first place?

The dark tourist experience

The following story is completely fictional.

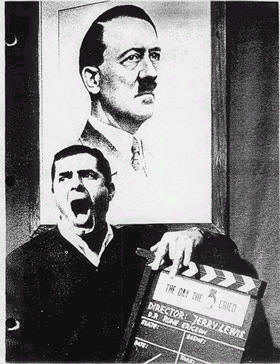

"Guards are assaulting the prisoners: beating them, spitting on them, slicing their skin with their Hitler Jugend -knives. The prisoners are begging: please, stop, no more! They are wondering what in God’s name they had done to deserve it. They are beaten with tycoons all over the body until there is no single solid bone in their bodies. They wither in great pain and finally drift away to silence. The guards have them thrown away outside to a ditch like dead animals. Only a pond of blood reminds the victims once were there."

Whether this incident was a video clip, part of a short story, or any portrayal at all, it seems impossible to find anything pleasurable in viewing it. Could the viewer actually get excited of seeing something like this? It is difficult to imagine; the mind is naturally prone not to think about it because it is naturally programmed to seek away from personal suffering and pain. Is there another way to look at it?

As Goldstein reports: "Reactions to displays of violence specifically may be considered enjoyable and wholesome if they are deemed mediated by identification with a successful aggressor." The aggressor, in this case the guard, is a very powerful person just there and then. He has the divine power to decide whether the prisoner should live or die. There is no way the prisoner could stand up to the armed guard. The guard can do anything at all and walk away clean without needing to expect any consequences. Placed in a safe setting like a movie or a sanitized portrayal of death with sufficient distance to reality, the observer may actually be able to enjoy the show. Goldstein emphasizes the fact that the attainment of pleasure from violent spectacles requires identification with aggressors and victims, whether they fight for justice or not:

"-- people identify with fictional heroes, but also with the crudest of fictional villains, in order to attain "vicariously" the gratifications that these agonists experience. Through such identification, it is said; people transcend their limited personal experience" (Goldstein 1998: 163).

Goldstein also claims that the dramatic exposition that dwells on violence is thought capable of freeing the consumer from conjectured fears and phobias, distrusts, and ill emotions. Also here, identification and vicarious experience are the keywords. (Goldstein 1998:184) This miraculous cleansing is deemed to happen through a cathartic experience when the consumer has finished watching a tragedy.

As Goldstein seems to stay strictly in the world of fiction when posing these claims, could it be possible that also non-fictional portrayals of violence and death could induce similar experiences? The undeniable popularity of the videos about traffic accidents from light car crashes to fatal collisions and clips of people getting hurt and even dying on-screen, all of which can be found in abundance on the Internet, shows not only that is it possible to enjoy portrayals of real death, but that it already is popular entertainment. Can we comfort ourselves with the notion that the people who watch this kind of entertainment do it solely for empathy for our fellow humans? Obviously we cannot.

However difficult it is to measure the pleasurable emotions in observing violence and death, not to mention finding its core causes, we should at least give it a try. If there is, as hypothesized, excitement of some sort in the experience of a dark tourist, there also has to be an explanation.

Enjoyment of observing death

There have been some scientific, and also rather unscientific attempts to find the causes for the enjoyment of observing portrayals of death and violence. As previously shown, the pleasure doesn’t necessarily arise from observation of death itself, but from identification with the villains and victims involved. The theory suggesting that the gratification comes from the person being able to transcend, in other words to rise above his personal experience through an aggressor or victim, is not enough to form the complete picture and it is surely not the only explanation.

Some quite mystical accounts adding to the transcendence theory have been made. Huxley (1971) refers to the radical inadequacy and isolation of human existence to argue the rewards attainable through interfusion of self and other. "Ideally," Huxley states, "one would recognize and feel this interfusion with the company of Good and the Just, with saints, angels, and the Deity. Alternatively, one might hope to feel at least oneness with all of humanity. However, one can also transcend normal existence through feeling the interfusion of one's existence with the Evil and Unjust, with vampires, demons, and Satan". It is transcendence of this kind that exposure to brutality and terror is supposed to foster. In common language, the feeling of being together with the Evil could bring one to feel like he is something greater, and so bring satisfaction. (Huxley 1971:67) How the interfusion with Evil can make one feel more powerful is not perfectly clear. However, increased amounts of self-mastery, control and competence through a ‘powerful’ ally could certainly satisfy some needs (see Self-esteem needs on the Travel career needs ladder). The interfusion with a greater power could thus help to fill a void that emerges from the need to have purpose in life and a feeling of being part of something greater.

Another interesting viewpoint is that of Dickstein’s proposed in 1984. Dickstein suggests that, as we are brought up, from childhood to adolescence to adulthood, we are taught to repress our fears and superstitions and to believe that the society will protect us. If we do this, we are taught, others would too. Dickstein goes on: "But in some level we never really believe this". He argues that literary and cinematic terror makes us vicariously seek for ways of coping with the insecurity, which is caused by the disbelief in being safe: we don’t actually trust in being secured by the society.

It is claimed that displays of violence help people deal with real fears of things that come from within and from outside and even to enable them to rehearse their own deaths. Moreover, these displays are said to "help audiences to confront personal guilt indirectly, so that they might break free from real or imagined sins through the controlled trauma of the experience". (Rockett, 1988: 3) Controlled is the word that needs to be stressed here. It means that no matter what happens in the setting, the viewer/partaker can walk away freely at any time, should the anxiety pour over his limits. There is a great resemblance with dark tourism: a few hours visit to a site of death can already be mentally exhausting, but as the visitor knows that it will last only for a short time, or until he no longer wants to stay, the stress can be sustained. After the visit, it is relieving to jump on the bus and leave the gory place behind.

If there is distrust in the society’s ability to keep us safe and we are therefore subconsciously feeling unprotected, watching death and getting close to it in order to create a feeling of safety might seem quite far-fetched. On the other hand, as common-sense psychology lets us assume: we are afraid of the unknown. In the present-day society, this is what death and dying really have become. Through becoming familiar with death and through understanding death and suffering, we could be released from the fear, and be able to restore death’s place in the circle of life. This would free us from escaping from death and so result in decreased amounts of anxiety within ourselves. Perhaps in this way, it is possible that we are able to experience relief at displays of death and suffering.

Let us move our attention to a real event in history, to the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963. Would it be frightening, thrilling and somewhat eerie to be sitting in his car when it all happened, even if you knew it was a just a repetition of the actual events and you knew already what was ought to come? Anyway one looks at it, for some the experience could indeed be exciting to varying degrees, depending on the individual of course. Similarly exciting as in the combination of fear and excitement when you are about to do the bungee jump, or when speeding with the car so you can feel the adrenaline rushing all through the body. They all offer thrilling experiences, no matter what the context.

Hence also the imaginary dark tourist’s experience, whose sole intention is to meet death and the macabre, could be simplified down to sheer thrill seeking. In this case, it is the encounter with death that is at the very core of generating the mental stimuli, thus relevant to account fully for the travel motivation. This is quite a generalized explanation on why the macabre has become a product for consumption, but it is laid on a solid need-based foundation. People require sufficient amounts of physical and mental stimuli in order to feel contented, discontentment leads to seeking of additional stimuli. It can be said that in regard to stimulation, there is also a balance state that the mind aims to reach. But it is also dependent on the individual’s previous experience: the level of stimulation that was enough in the past will not be sufficient to satisfy the need in the future.

Theories tracing the origins of the sensation in the face of death and suffering are various. Based on the accounts stated before and mixed by the variables of individual interpretation and the type of a dark tourism destination, it is clear that a unifying theory is undoable. Therefore, we must be satisfied with a number of explanations that, from their own perspectives, contribute to explain an individual experience.

Personal interpretation

We all interpret what we observe, in this case portrayals of violence and death, according to our own experience and according to the context it is displayed in. If the fictional story written before were a video clip of an old action film placed in a prison environment, it would be somewhat meaningless to us. If we knew it was a true story from the Killing Fields with real people in it, we would be likely to feel pity and perhaps anger. If, taken still a step further, the prisoner had been our grandfather and it was a true story of his last day, the reaction to the display would be completely different. Should our grandfather have been the guard, yet another interpretation of the same event would emerge.

Similarly, those who have a connection to the Holocaust on a personal level through a family member for example, are prone to react differently to an exhibition about the Holocaust to those who have no connection to it at all.

People are also different in sensitivity. For some, violence on television is too much to watch, while others view it as entertainment. Head chopped of a villain may be ‘cool’ to a teenager, whereas his mother watching the same program is forced to turn her eyes away. If we have seen much violence and dying on television, it is possible we don’t react unless the film is extremely cruel and wretched, enough to make the head spin. On the other hand, having witnessed much real suffering and dying may also make the person hypersensitive towards portrayals of death and violence, real or fictional.

Different dark tourists can hence have a myriad of different experiences when visiting a dark tourism destination, depending on their past, connection to the event, and their personalities. Also the company the dark tourist is travelling with can affect the experience remarkably. Group tourists and individual travellers can have big differences in their experience.

Nonetheless, it is not only psychological factors that form the dark tourist’s experience. Time too can change attitudes and our understanding of past events.

Effect of timely distance

As learned in defining the phenomenon of dark tourism, time is an important factor in the interpretation of past events. According Lennon & Foley, dark tourism is an intimidation of the very foundations of modernity (2000: 11).

Human rights, modern technology and science have all been abused in the past in order to gain control, wealth or territory. Many such events have ended up with tremendous human suffering and tragedy and many of those places are now dark tourism destinations. If we think about medieval wars and the barbaric executions of the era or gladiatorial fights far in the past, they do not shake the picture of our current world. This is because they are so far apart in time from the contemporary world that they cannot be fitted in the current context. Thus there is no anxiety or worry about the modern society and the visiting such a site will not result in inner turmoil.

Martin Luther King was a symbol of equality and thus a symbol of modernity. He was the embodiment of all that the Ku Klux Klan despised. In 1968, he was assassinated and the people’s picture of the civilized, equal world was turned upside down. This event is in the past, and yet it is so close that it could happen again. Moreover, still after the Second World War, mass murder and genocide have happened in many parts of the world. This is an obvious source of anxiety in our current world and as such it fully satisfies Lennon & Foley’s requirements for a dark tourism destination.

As a generalized guideline, we can say that the closer the dark event is chronologically, the stronger the impact and the darker the dark tourist’s experience.

Dark tourism and curiosity

Having stories from friends, documentaries on television and numerous references to destruction, suffering and dying presented allover in media, it is not surprising there is so much interest in the hard side of life. As people have been introduced to a topic, they are often prone to find out more information about it: people are curious by nature.

Curiosity is more or less a natural instinct; curiosity confers a survival advantage to certain species. Curiosity is common to human beings at all ages; from infancy to old age, and is easy to observe in many other animal species. Many aspects of exploration are shared among all beings and present in everyday life: babies readily taste anything they get in their reach and the first thing dogs will do when entering a new premises is sniffing all the corners. Strong curiosity is said to be the main motivation of famous scientists. In fact, it is mainly curiosity that makes a human being an expert in a certain field of knowledge.

Many things are also interesting to us only because they are rare or unusual. Discussing people’s interest for violent entertainment, Carroll suggests that horror films do not so much discharge negative emotions as appeal to our curiosity: "horror attracts because anomalies command attention and elicit curiosity" (1990: 195). Horror movies present society's norms only to violate them. This violation of norms holds a fascination for people to the extent that they rarely see these violations in everyday experience. The prevailing norms in today’s society are supporting freedom of speech, equality and individual rights, for example. Many events that dark tourism memorials and sites stand for were to violate these and many other norms and often ended up with loss of many lives or even mass murder. Hence dark tourism destinations could be thought of sites that simply satisfy our curiosity above all.

Morbid curiosity is a term often used when discussing dark tourism motivation. It is a compulsion, a drive fixed with excitement and fear to know about macabre topics, such as death and horrible violence. In a milder form, however, this can be understood as a cathartic form of behaviour or as something instinctive within humans. This aspect of our nature is also often referred to as the 'Car Crash Syndrome’, arising from the fact that is seems impossible for passersby to ignore such accidents. (www.wikipedia.org)

Before applying the presented theories to explain the dark tourist’s behaviour, let’s take a visitor’s view on real dark tourism sites. This is meant to help in understanding the dark tourist’s experience in similar places: places of torture, dying and saddening human fates.

Places of dark tourism

The descriptions in this chapter are grounded primarily on the author’s personal visits to the sites during spring and autumn 2006. Having observed these sites of human tragedy contributes to more detailed descriptions and hopefully also to a better understanding of the atmosphere typical at this type of dark destinations. Source materials acquired from the sites and personal discussions with the employees/site managers were used to build up the sites’ histories and factual framework.

Killing Fields of Cambodia

It was year 1975 in small peasant country of Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge had seized power in guidance of their leader Pol Pot. During the first few days after Cambodia had become Democratic Kampuchea, all cities were evacuated, hospitals cleared, factories emptied, money abolished and monasteries shut. The goal of the new rule was to turn back the clock in Cambodia and make it ‘the number one communist state’, following the example of Mao’s China. They planned to expel or destroy existing social groups, for example, people of foreign origin, education or employment.

On its quest for total power in the country, Pol Pot’s Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) felt no pity. One famous motto, regarding the New People, was: "To keep you is no benefit. To destroy you is no loss." New people meant civilian Cambodians. Anyone who had been living in the urban areas before 1975, were forced to move to rural areas and were made a New Person. Under the communist regime, approximately 1,7 million people perished. They died of executions, starvation and forced labour. (Kiernan 1996: 8, 27)

The notorious interrogation centre S-21 of the Khmer Rouge in central Nom Penh (capital of Cambodia) was used to imprison people, usually for some months. During this time they were ferociously tortured. The purpose was to force confessions out of them, so they could then be exterminated in the Killing Fields just outside the city. Out of 17 000 prisoners in Tuol Sleng, seven are known to have survived.

Nowadays the Tuol Sleng prison and the Killing Fields are popular tourist destinations in Cambodia. The prison has been converted to a museum, though it is very plain and simple in presentation. Before the Khmer Rouge coup d’etat it was as a high school. The former cells / interrogation rooms have metal bunks in the middle of the room and a photo on the wall showing how the prisoner was tortured or simply its result: a dead corps. Some of the rooms have torture instruments such as metal rods placed on the bed.

The Khmer Rouge took a photo of every prisoner in S-21. These photos are arranged onto big boards in the second building of the museum. The eye-to-eye contact with the victims causes the biggest impact on the visitor. The faces are grave; some of still show a glimpse of hope, some eyes have already dimmed. There are faces of young children and men and women at all ages. On the second floor of the second museum building there are biographies of both former prisoners and officers at the Tuol Sleng prison. The third building on the right side when looking from the entrance gate offers more pictures and a repeating short film telling more about the mass murder of the Cambodians. On the way out it is possible to buy literature about the event in a kiosk placed inside the – frankly said – quite a beautiful courtyard.

Once you have visited the Tuol Seng prison, you will logically continue to the Killing Fields about twenty minutes to half an hour drive away on a moped taxi (a popular and affordable means of transport in the area). The dusty and bumpy rural roads lead you to Choeung Ek, where at the end of the road it is difficult even to say you are at the site of mass murder. The site itself – where 17 000 people were executed – may seem surprisingly small. Quite much in the centre of the site there is a small tower-like building stacked with shelves. When you get closer to it, you notice something extraordinary: over 8000 human skulls are put on the shelves, arranged by age and gender. On the floor under the shelves there are the clothes of the victims, cleaned and put there after the excavation of the mass graves in 1988. One may start to wonder: is this kind of presentation necessary? One thing is for sure: it is powerful.

An open-air building some tens of metres away from the white tower offers a detailed map of the site and has further information on several large glass-covered boards hung on the wall. Not far from either one of the buildings there are several hollows in the ground. The information plates tell they are the pits where the victims were thrown after execution. Half the corpses now lack heads, which are presented in the white tower. Under some of the trees, there are human bones still lying around like wooden sticks. Until now, most visitors have seen enough of the Killing Fields. A bookshop selling books about the mass murder and genocide is just outside the compound.

The prison in Nom Penh and the Killing Fields are positioned at the darkest edge of the dark tourism continuum. On average 200 visitors visit the Killing Fields per day. The surprising fact is that only three per cent of these visitors are Cambodian. For comparison, in Auschwitz-Birkenau the host natives constitute one third of all visitors.

The Killing Fields and Tuol Seng are very plain and are not at all commercialized apart from the book sales on-site and the possibility to engage a guide. These can hardly be called commercialization either, since their main purpose is education, not moneymaking. The authentic nature of these dark sites increases their appeal among dark tourists. The Killing Fields have come to stay.

The River Kwai Bridge

The River Kwai Bridge was a part of the railway built by Allied prisoners of war and Asian workers under the Japanese occupation during 1942-43. The route was planned between Kanchanabury in Thailand to Moulmein in western Burma to support the Japanese occupational forces in Burma and the planned invasion of India.

The quarter of a million people forcedly or otherwise employed people were living and working in varying conditions at the construction camps. Often there were shortages of food, medical supplies and sanitary facilities. In many cases the camps were a living hell. The working days were inhuman and in the tropical climate many deceases were lurking for the malnourished and exhausted labourers: malaria, cholera and the tropical ulcer were common.

During the sixteen months of construction of the 416 km track, a hundred thousand workers died. Some other estimations about the death toll are much higher. There are three museums dedicated the horrors of the Thai-Burma Railway, two of which are at the other terminal point in Kanchanabury: the Thailand-Burma Railway Museum, opened in March 2003, and the JEATH War Museum.

The JEATH War Museum (Japan, England, America, Australia, Thailand, Holland) is an open air bamboo hut museum on the bank of the Mae Klong River and has been built as a copy of an original prison camp and established to collect various items connected with the construction of the Death Railway by prisoners of war during the Second World War, 1942-1943.

The museum is divided into two sections: Section I and Section II. Section I displays a lot of pictures of the prisoners of war during their real life in the camp and Section II displays the instruments that the prisoners of war used while they were in the camp.

The first thing that strikes you when you visit the museum is the bamboo hut with a collection of photographs displayed. The hut is a replica of the conditions the POW's (prisoners of war) were forced to live in. The museum displays graphic images of the terrible conditions inflicted on the many men that died and the many that survived. To bring these atrocities to the public domain, the museum exhibits many photographs taken of real situations either by Thai's or POW's. Alike other war and death-related museums, there are also many real accounts written by former POW's, their relatives and friends.

Not a long drive away from the museum, there are the remains of about 7000 war prisoners put neatly in a cemetery. From the bank of river Kwai it is possible to take a scenic train ride on the Death Railway to get a good look at the railway and the sceneries around it. Many tourists can also be found walking along the bridge on a sunny day, posing and taking pictures with the infamous river Kwai in the background. (Image Makers 2005: 10, 15, 18, 25, 41)

Focus on Auschwitz

This chapter is an introduction to the history of the largest of Nazi death camps and at the same time, a descriptive analysis of the most infamous dark tourism destination. The author visited Auschwitz in October 2006 mainly for research purposes, but there was plenty of time for observing people visiting both the museum and the camp sites. School children, adults and elderly; Jews, Christians and Muslims; Poles, Germans and Americans; teachers, doctors, historians; married couples and singles; men and women: people from literally all walks of life could be seen visit the Museum each day. Auschwitz has become (or more correctly: has been made) an emblem of tolerance, individual freedom, equality and unity of mankind. It stands for all that once was punishable by death.

Camp history in short

The site of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the Nazi death camp in Oswiecim, Poland, is the best-known place of martyrdom and destruction in the world. This camp has become a symbol of the Holocaust, of genocide and terror, of the violation of basic human rights and of what racism, xenophobia, chauvinism and intolerance can lead to. The name of the camp has become a synonym for the breakdown of modern civilization and culture. (Swiebocki 2003: 6)

The Nazi vision of the thousand-year Reich envisaged a whole new Europe. Germans and the Nordic blood were considered superior to anything else, and hatred of democracy and Marxism were prevailing ideologies of the Nazi regime. Another fundamental principle was the Germans right to Lebensraum (living space), which meant to extend far beyond the German borders. The Jews were the main targets of extermination to achieve a ‘racially pure’ state, but the purification extended also to other groups, such as the mentally challenged, homosexuals and the Gypsy people.

The SS (Schutzstaffel, German for Protective Squadron) founded Auschwitz in the spring of 1940 as a concentration camp, similar to those that already existed in Nazi Germany. Following the occupation of Poland in 1939, the mass arrests of Poles had filled all the existing prisons to overflow. A camp was suggested to be set up in order to keep up with the flow of political prisoners. The 20 prewar barracks in the town of Oswiecim in southwest of Poland were found suitable for the purpose as no construction work was required and the town had convenient road and railroad connections. These reasons encouraged the Nazis to expand the camp on an enormous scale. After the first political prisoners arrived at Auschwitz on June 14 1940, by mid-1941 also Soviet POWs, Czechs, French and Yugoslavians were being sent there. These deportees consisted mainly of the intelligentsia and other ‘dangerous’ elements of the occupied countries, amongst them a number of Jews.

Auschwitz started to serve a second function in 1942. It became the largest extermination camp in the Third Reich. In its operation from 1940 to its liberation in January 1945 approximately 1.5 million people were murdered in the camp. Most of the records were destroyed prior to liberation and thus it is impossible to know the exact death toll. Gas chambers became the notorious instrument for mass murder. At least 1 100 000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz and on the physical examination of the SS doctors upon arrival, 70-75 % of the newcomers were sent to death in the gas chambers. In most part, they were elderly, women and children and those otherwise considered unfit for hard physical labour. If prisoners were not executed or gassed, they usually died of plagues, malnutrition, physical abuse and occasionally of the inhumane medical experiments conducted by Dr Joseph Mengele. (Swiebocki 2003: 8)

Establishment of the museum

Months after the end of the Second World War and the liberation of the camp, a group of Polish survivors from Auschwitz began to spread the idea of establishing a museum in memory of the victims of the death camp. In July 1947 the site was called into being as Oswiecim-Brzezinka State Museum, secured by a law to protect the grounds.

The museum’s task was to secure the grounds and buildings of the camp and to collect and gather together evidence and material related to the Nazi crimes so that they could be studied and made accessible to the public. There are 154 original camp buildings in the Museum and Memorial (56 at Auschwitz I and 98 at Birkenau).

Thousands of objects belonging to the people who had been doomed to die were found at the site of the camp or nearby after liberation, including suitcases, Jewish prayer garments, artificial limbs, cooking pots, glasses, shoes and tonnes of human hair. All of these amongst many other exhibits are on display in the Museum.

Auschwitz museum is very active in its quest for educating the public. The Museum carries out scholarly research, organizes exhibitions shown in Poland and other countries, issues its own publications, organizes lecturers, conferences, seminars, and symposia for teachers and students from Poland and other countries and offers a year-long postgraduate course for Polish teachers on Totalitarianism, Nazism and the Holocaust. Most of the education happens nevertheless amongst the visitors to the Museum. Up to date an estimated 28 000 000 people have visited the museum.

The mission of the museum is not only to present the history as it happened, but also to make people remember the victims of the camp through not only the statistics but as real and individual people, who suffered extraordinary atrocities and for the most part, passed away here. Anniversary meetings are held to gather former prisoners and their families, government officials and media together to learn over again about this important lesson in our history.

Inside the museum

Both the former concentration camps Auschwitz I and Auschwitz-Birkenau are accessible to the public. Places in the camps where specific events have taken place are marked with black granite tablets with descriptions and pictures from the time the camp was still in operation. They help the visitor better to understand what happened there, since much was destroyed by the Germans when they fled from the approaching Red Army. The remains of gas chambers in Birkenau (blown up with dynamite) are described with this kind of tablets and between the ruins there is the International Monument erected in 1967. The grand monument was built on top of the railway track that led to the Crematoria IV and V further away.

Several buildings at Auschwitz I are used for the so-called national exhibitions and the general exhibition. The national exhibitions illustrate the life and fate of the prisoners from different countries who were deported to the camp. The general exhibition consists of the collected objects that once belonged to the prisoners.

It is mostly school groups and other groups that pervade the silent alleys between the cellblocks in Auschwitz and amidst the wooden barracks in Birkenau. From about ten in the morning onwards the museum in Auschwitz I is full of people: school children, tour guides, and interested by-passers walk around in the museum waiting to go on their scheduled tour. The clerks working at the information desk are very busy coordinating tour guides to different groups. The atmosphere feels as if it were any ordinary museum. All visitors know however that this is a place where people were murdered by the thousand, and hence some caution can be sensed in the air. After the visit some seem relieved, others clearly anxious. The usual way to visit the museum is to start with Auschwitz I and then move on to Birkenau afterwards. A free shuttle bus connection is established between the two camps. In the vastness of the Birkenau camp, where up to 100 000 prisoners could be held at one time, groups and scattered individual visitors move along the railway track and wander around the empty barracks that used to house the prisoners. About 90 % of the barracks in Birkenau had been destroyed, but the ones that remain unveil the horrendous living conditions the prisoners had to face.

Information tablets are placed along the recommended route of visitation to allow the visitor to get a grasp of what happened and where amongst the numerous similar barracks.

Auschwitz is still a place of horror, even though the factories of death, the gas chambers and crematoria have not been active for over sixty years. Nevertheless, that time is reawakened to anyone who visits the museum and gets close to the unimaginable terror that once ruled there. Visitors’ motives and feelings to this site are measured and discussed in the next chapters.