Tuesday, 19 May 2009

Air Doll

Michael Guillén: Congratulations on being selected for this year’s Un Certain Regard with your new film Air Doll. I’m interested in what you were seeking to explore thematically in your latest film?

Hirokazu Kore-eda: The doll is inflated with air, so it’s basically empty or blank inside. She is living in Tokyo and around her are us urbanites who are also empty. We have nothing inside of us either and we are isolated. I wanted to explore the emptiness, the loneliness that is felt by the inflated doll and the isolated urbanites.

Monday, 18 May 2009

Contact Zones

What I got out of the subcultures book was the importance of Mary Louise Pratt's concept of "contact zones". I haven't followed the music blogosphere closely enough in recent times to check if the debates about a British "hardcore continuum" referred to Pratt. But if they didn't, it strikes me as unfortunate because another conference recently made use of her work in a way that appears mutually beneficial. A lot of similar questions were asked, and one can even find terms such as "centrifugal" and "centripetal" approximating Simon Reynolds' response to critics on his Energy Flash blog. Moreover, the Contact Zones in Modern British Culture conference specifically refers to musicians to flesh out its arguments!!

Just in case anyone happens to read this who was a participant, or has already read about both events, my apologies if what I have to say here is not exactly news. Part of the problem for me is that I find wading through the Continental philosophy and/or musical blogosphere too offputting. To be more precise, whenever I read such a blog dutifully reporting the details of the latest esoteric subject, [to cite an actual example from Infinite Thought], as per a seminar on the problem of time in Hegel, "moving towards an historical ontology of the social", my first instinctive reaction is usually a series of vivid hallucinations akin to Francis Bacon's depiction of the Pope frying in agony on the electric chair. The telling difference from Bacon's original though is that I've taken the Pope's place and the electric chair is in the seminar room. So unless there is adequate scope for such a reading method to dialogue with a social epistemology, I generally won't feel the stakes are sufficiently high enough to warrant the risks to my mental and physical health, which would surely follow from a more protracted encounter (i.e. I'm only attracted to those debates that are able to also encompass issues of epistemic justice. An example of a precedent would be unpacking how and why the Hegelian Alexandre Kojeve became a neocon guru).......OK, I admit the severity of my reactions as described here were somewhat exaggerated for comical effect, but you still catch my basic drift, right?

For now then I'm inclined to await publication of conference proceedings to gain a firmer conceptual grasp on "contact zones". I believe Pratt's considerable endeavours are potentially complementary to the theory and method of articulation, as originally developed by Stuart Hall: for researchers interested in musical genres and scenes, it brings into alignment (i.e. contact) the elements that constitute something like the analytical program known as the sociology of rock, in a manner that will [of course] change on a case by case basis.

Saturday, 16 May 2009

Peter Frohmader, H.R. Giger & the "Alien" soundtrack that almost was....

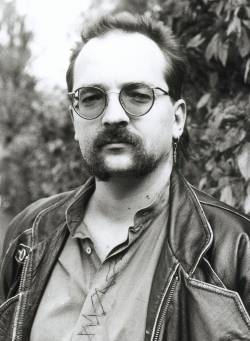

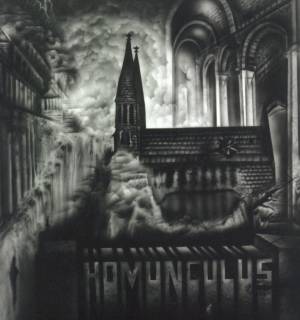

One of the first things that attracts the attention most in his paintings, is the use he makes of black and white to enhance certain themes or elements. Thus for instance, his landscapes of narrow medieval streets look like pictures extracted from accursed books, and his ghostly Gothic cathedrals have an undeniably evil aura. Looking at some of those black and white elements, as for example the entire series of "Homunculus", it must be admitted that in full color they would not be so very impressive. He also incorporates this technique into photography and even to his own person, and decides he is one of these elements that must appear in black and white. Therefore, he always prefers photos to show him in black and white, instead of color.

Some of his illustrations, as for instance the mass of human remains that presides the cover of his first album, or the poster that is included in his second album, show his vincle to death and Beyond. He sees these universal enigmas as a key for his creativity.

Some of his illustrations, as for instance the mass of human remains that presides the cover of his first album, or the poster that is included in his second album, show his vincle to death and Beyond. He sees these universal enigmas as a key for his creativity.

In a great part of his paintings there reigns a nocturnal atmosphere, perhaps enhanced by the timetable of his artistic work; Frohmader has produced his works mostly at night, at least in the past. And an oneiric texture, nightmarish in nature, pervades these paintings as well, so as to try harvest some of the essence of bad dreams, by means of atavistic, ancestral signs, from terror. The final effect is to reflect the things that each observer of the painting would swear to have dreamed in some nocturnal nightmare.

Nevertheless, his work is not as dark as many people believe, and this is an important point. Frohmader has become famous as an "accursed artist" because the most remarkable part of his art is the sinister content, and therefore, this is what is more popularized. In his music there also are passages of light and beauty, a sincere message as opposed to the commercial productions that have appropriated the term "New Age".

In his paintings, he shapes cosmic adventures where the observer can contemplate lakes and rocks made from light, the origin of life fused with the birth and death of suns, exuberant jungles spreading to the horizon, intergalactic starscapes swept by the cold light of nebulae, or simply the Sun rising from the clouds and shedding its light after a storm.

Up to a certain point, the dark and light aspects of Frohmader's art have a chronological distribution throughout his career. And thus we have that in the first years darkness, the macabre, the evil dominate; while in his latter years it is light, beauty, the cosmic, what takes the place of the former. Although in the mid 1980s, with "The Jules Verne Cycle" (two pieces based on two stories by Verne: "The Mysterious Island" and "20,000 Leagues Under the Sea"), this subtle change can already be appreciated, it isn't until 1988 with "Spheres", when Frohmader leaves the dark regions and makes a cosmic voyage towards the worlds of light. This new artistic and aesthetic concept continues in the CD "Miniatures" (1989), whose cover is a painting on the wave of the German futuristic trends of the 1920s - 1930s; as well as in 1990, in the CD "Macrocosm" (released in the United States). The final jump arrives with "3rd Millenium's Choice Vol.1", which closes the circle, and which in a way means a return to the original starting point, even though from a different angle. By the end of 1990, he engages on a trip to the French Brittany, so as to find artistic inspiration and produce a 20 minute film showing landscapes and impressions in his personal style, including music. This music is included in his CD "Armorika", running time 74 minutes, released at the beginning of 1991. The result is a very dense, imaginative work, specially in the themes "Tumulus", "Les Roches du Diable", and "Dolmen". At the beginning of 1992, his CD "3rd Millennium's Choice Vol.2" is released, a meditative excursion that enters science-fiction rather than terror. Later, new, excellent works appear.

COLLABORATIONS, CONTACTS AND INFLUENCES

COLLABORATIONS, CONTACTS AND INFLUENCES

He is a good friend of Florian Fricke, the alma mater of the mystic music band Popol Vuh, known for their cosmic music since the early 1970s, as well as their movie soundtracks for German movie -maker Werner Herzog at an international level.

Musically speaking, he has collaborated with Ax Genrich from Guru-Guru, and Christoph Karrer from Amon Düül-2, members from two legendary bands of German psychedelic music, predecessors to the New Age movement. In his recordings sometimes collaborate violinists Stephan Manus and Iva Bittová, Stephan Seithel (Oboe), Birgit Metzger (vocals), and others. Through Nekropolis Records, his record label, he has produced CDs from other interesting alternative musicians, as for instance Andreas Merz and Gerd Schedel (two electronic experimental composers from Munich), and Gulaab.

He has worked with the painters of contemporary fantasy art Ernst Fuchs and Hellmut Neukircht; and he has been in contact with sculptor Martin Schöneich as well as painters Wolfgang Ohlhäuser and Elke Wassmann.

Among his influences we find the Gothic horror movies from silent movies, as for instance the "Nosferatu" by Murnau, besides the metaphysical science-fiction movies from Russia and Poland, among them "Solaris" and "Stalker". As for the writers who have influenced him most, these are: H.P. Lovecraft (whom he has illustrated), Edgar Allan Poe, Clark Ashton Smith, Henry James, Bram Stoker, Algernon Blackwood, among less known ones. Besides Giger, the painters who have influenced him most are Bosch and Grünewald."

Excerpt from "The Oneiric Prospections of Peter Frohmader" by Jorge Munnshe

Toshiya Ueno

While the provocative claims in that interview perhaps remain open to debate, I have to admit to a factual error in the palingenesis post. It wasn't actually Tangerine Dream who contributed the "stunning" track to the opening of The Keep. It was a demo by Brian Eno. If you listen to "Mea Culpa" on My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, it's possible to hear traces of The Keep. Unsurprisingly then, Tangerine Dream have never covered or performed live the track in question, and this also explains why it hasn't appeared on the official soundtrack. It has apparently surfaced though on a bootleg called Ghosts, which thus far I've not managed to track down.

Some other thoughts unexpectedly came to me reading Dennis Cooper's tribute to Whitehouse. I was less interested in Cooper's personal identification with their libertarian aesthetic, or the mentioning of Bennett's claim that Rip It Up & Start Again mistakenly reports a joke by Steve Stapleton as if it were a factual statement about the band's interest in certain extreme pornographic publications, than in how he reminded me that Paul Hegarty had not only edited a book on Dennis Cooper, but has written a couple of books about noise/music as well.

It also just so happens that I've been listening to Merzbow's 1930 a lot recently, so I'm wondering derridata if you might be able to bring these reflections full circle by answering a question? Have you encountered any commonalities, in theoretical terms and artefacts used as examples, in the respective writings of Toshiya Ueno, Hegarty on Merzbow, and the cultural studies of anime you've been undertaking? Don't worry, I'm not asking you to chase down these authors, but simply wondering if their names have cropped up during the course of your research? If you have any thoughts on the matter, please feel free to hold them till we hook up at the Brian Eno gig. I figure they might have to do with topics such as "techno subjectivity" and, by extension, "post subcultural" spaces or "scenes" in which such identities are enacted/performed/consumed. I'm wondering also whether the existence of any such commonalities could serve to undercut those in the music blogosphere who are focused on divorcing "genre" from "scene"?

One more thing relating to animation, I like how this clip critically comments on not only human motion in general, but more specifically the treatment of "older" women by consumer culture:

Friday, 15 May 2009

Civic War

Review

Product Description

Dietrich Scheunemann

Be this as it may, I couldn't resist putting up something about one of my favourite topics: the politics of the avant garde. My reflections are spurred by noticing a lot of stuff in the blogosphere of late (i.e. in the Continental philosophy meets avant garde music blogosphere) debating the claim that capitalism has now accelerated to the point where cultural innovation has become exhausted. This occurrence is then used to explain why creative energies have [allegedly] lain fallow in popular music.

By way of a response, two central questions have arisen for me. Firstly, how can these claims be qualitatively and quantitatively differentiated from the posthistoire trope that has characterised modernity even long before Gehlen's proclamation in 1963 of a state of "cultural crystallisation"? If they can't be, then it is difficult to see that there is really anything unique about the current state of affairs. I suppose one available option is to ascribe causal primacy to an intensification of the forces of production, leading to programmatic interpretations of the relationship between base and superstructure, and even the "virtualization of the human". This approach, which is dubious because of its reliance to varying degrees on forms of technological determinism, constitutes the essence of "cybermaterialism". In these terms, the bloggers in question are in effect describing a formal correspondence with the musicians they write about, who can now more freely sample and manipulate sounds through digital means, much in the same manner as the blogger who is able to cut and paste hypertext. So culture eventually becomes recycling rather than innovation. This state of affairs is then quickly generalised to encapsulate our collective, inherited historical fate.

In the latter form reference is made to "the postmodern condition" and/or "the information age". And so to my second question: I wonder if the story would be so neat if the quantitative/qualitative issues I've raised were mapped to a cultural sociology of the avant garde? One of the major reasons I say this is that so many of these discussions in the blogosphere are framed with reference to Fred Jameson's thesis, without having acknowledged its inherent problem as pinpointed by Dietrich Scheunemann: Jameson conflates postmodernism and avant garde. So I'm forced to agree with Scheunemann that there is plenty of scope to test the heterogeneity of the avant garde's creativity, which can then be compared and contrasted with resurgent notions of "posthistoire". But it's also not sufficient to adduce evidence from one facet of the arts, as this simplifies the myriad of network relationships the avant garde (s) have attempted to involve themselves in over time, with varying degrees of success. This fact explains why Scheunemann was involved in a working group that produced around 21 books and anthologies on the subject. The extent of this activity hardly attests to an exhaustion of creative energy.

My own thought is that the avant garde will continue to perform its usual role for popular culture: a kind of weather vane offering advanced warning of impending conditions. We'll thus continue to see pioneers receiving belated recognition by their successors, who have managed to synthesise the original's creative approach into a more palatable popular form, thereby reaping the financial rewards in the process. But before leaping to the conclusion that this is only a pessimistic lesson about the taming of radical impulses, I would recommend weighing up the breaks, as well as the continuities. Reading Scheunemann as well as David Hopkins' (ed) The Neo Avant Garde is a positive first step in this direction.

The next step is to qualify the extent of "cultural exhaustion" by acknowledging how our common beliefs and interests may "constitute a res publica: a virtual public sphere that unites the critic and the criticized in a common fate in the empirical world" (S.Fuller, The Knowledge Book, p. 16). The inference that may be drawn from Fuller, with reference to the blogosphere critics I've discussed here, is that they have failed to play the social epistemologist's role of the interested non-participant. Were they to have followed Fuller's dictum, a greater sense could have been imparted of how "the relevant res publica may shift according to whom the critic is criticizing". Instead, a high degree of narcissistic identification between bloggers and musicians hypostatises the dilemma of all avant gardes with no troops left behind them. Or rather, as an exasperated Raymond Williams wondered aloud (when responding to Stuart Hall's diagnosis of "the toad in the garden"; i.e. Thatcherism), "will there be no end to petite bourgeois critics making long term adjustments to short term situations?"

Sunday, 10 May 2009

Saturday, 9 May 2009

Defending social theory in/from the blogosphere

Newsreel style theory....

It's certainly true that I've mentioned as well some limitations in Terry Eagleton's writing, but I love his review of Peter Conrad's Modern Times, Modern Places. In this instance he manages to offer a succinct appraisal of the key features of cultural journalism. So what I'm wondering, mhuthnance, is whether what Eagleton says about Conrad would be readily applicable to another book we were discussing the other day: Alex Ross' The Rest is Noise? I haven't read Ross, but I own a copy of Conrad's book, so what I have to go on is the seemingly comparable scope of the two works: a grand tour through the culture of modernism. Could the tables be turned somewhat, to focus more on the practice of criticism, than what the book (s) purport to be about. At times like this I can't help thinking like a professional editor, by wondering about the intended audience. Such a rethinking would require a cultural sociology in a different register. Think, for starters, of Andrew Ross' No Respect: Intellectuals & Popular Culture, Eyerman and Jamison's Music & Social Movements (which uses Raymond Williams' concept of "social formations"), and Pierre Bourdieu's Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste.

I also haven't read Owen Hatherley's Militant Modernism, so I can't comment on how it stacks up against the aforementioned works, letalone Williams' posthumous The Politics of Modernism. But the background I have on Hatherley's book is [at least initially] a cause of some concern, given its connections to both the blogosphere and print journalism. I won't speculate further here about the possible merits of that work, but instead ask you, mhuthnance, to keep these passages in mind as a yardstick that could be used to evaluate Alex Ross. Maybe Ross will acquit himself really well, but here are a few of the pointers Eagleton teases out that I feel are particularly worth keeping in mind:

"The book’s method (emphasis mine) thus reflects its subject-matter: Conrad has produced a kind of Modernist montage of Modernism, a curved, centreless space in which any item can be permutated with any other. Each chapter is a mesh of connections but self-contained, so that in a Modernist smack at realist notions of narrative order, no chapter can claim priority over another. The form of the book is Einsteinian rather than Newtonian; indeed the Einsteinian world-picture is a subject it explores at length. Relativity, like everything else in the book, is treated relativistically: Conrad’s prose leaps mercurially from one cultural illustration of the doctrine to another, weaving an intricate web of relations in which they all come to seem indifferently interchangeable. If the book wasn’t so nervous of cultural theory, one might even detect in this method a trace of Walter Benjamin and Theodor Adorno’s notion of ‘constellations’, a brand of surrealist sociology which abandons hierarchies and abstractions and lets its general ideas emerge from the interaction of minute particulars. This, anyway, would be a charitable way of avoiding the conclusion that Conrad is just a good old empiricist who happens to enjoy Continental art.

...Modern Times, Modern Places is an astonishingly well-informed piece of work, which roams from ballet to Berg, Fritz Lang to Jack Nicholson, with the omnivorous energy of the Modernist art it addresses. But Conrad’s pithy style, which hardly stumbles for over seven hundred pages, also sails close to a sort of colour-supplement smartness, hovering somewhere between epigram and sound-bite (‘Freud’s thought turned reality upside down’). If his writing is pointed it can also be glib, covertly sensationalist beneath its clipped impersonality: early 20th-century Vienna possessed ‘a Jewish clerisy, excluded from power, which in revenge exposed the discontents suppressed by civilisation, released the empty air pent up in language, and dismantled the melodic scale’. A lot of the book is more high-class cultural journalism than rigorous inquiry. Social context is conveniently packaged, and though there is much play with scientists and philosophers, one doesn’t sense that the author could hold his own in a discussion of primary narcissism or perlocutionary acts.

With commendable impudence, Conrad refuses to disfigure his text with a single footnote, even if some readers may feel that he wears his learning too lightly. Unlike some avant-garde works of art, this book erases all traces of the labour which produced it. What is worrying, however, is less the absence of footnotes than of original thought. Conrad’s general ideas about Modernism are for the most part standard stuff; what is gripping is the intelligence with which he puts them concretely to work. But this vivid quiltwork of allusions lacks conceptual depth. Analysis gives way to metaphorical resemblances – a flurry of analogies which, as in the Martian school of poetry, are some times coruscating and sometimes callow.

In this, Modern Times, Modern Places is more Post-Modern than Modern. Modernist art may be allergic to absolute meanings, but it cannot rid itself of a dream of depth, plagued as it is by a nostalgia for the days when truth, reality and redemption were still notions to be reckoned with. If the Modernist artwork has shattered into fragments, what this leaves at its centre is not just a blank, but a hole whose shape is still hauntingly reminiscent. Unlike the Post-Modern work, the Modernist artefact cannot give up its hermeneutical hankering, its belief that the world might just be the kind of thing that could be meaningful. For Post-Modernism, by contrast, this is just a kind of category mistake, a scratching where it doesn’t itch, part of a post-metaphysical hangover which deludedly assumes that for a thing to lack a sense is as grievous as for a person to lack a limb. Post-Modernism, being too young to remember a time when there was truth and reality, is out to persuade its Modernist elders that if only they were to abandon their hunger for meaning they would be free.

Modern Times, Modern Places is Modernist in its allegorical habits but Post-Modern ist in its carefully contrived depthlessness. It is a brilliantly two-dimensional book, miles wide but only a few feet thick, which has all the virtues of what Eliot called an art of the surface.

Whatever its limits, his book communicates the exuberance of Modernism as few native English critics have managed to do, and does so with an elegance and concision in which each sentence strives to be an aperçu. If his analogies are sometimes strained, they are rarely less than suggestive. Modern Times, Modern Places tells the story of modern cultural history with unflagging freshness, and without an ounce of surplus stylistic fat."